SPAM Save America

The Original Zombie Food Idea

This month, I’m doing a workshop on food writing with prolific travel and food writer and New York Times opinion columnist, Diana Spechler. It’s been a great brain exercise and combines all three of my central loves — writing, food, and travel. For some reason, SPAM has been my Roman Empire for almost three weeks now. Enjoy.

When I was a kid, we always had a dusty tin of SPAM on the high shelf in the canned food cupboard. It was known as a “weird Dad food” among us kids, and therefore considered irrelevant. It sat alongside the jar of capers that I was convinced were baby snails, and pale green asparagus in a can of juice that already smelled like pee. Those foods were not on my menu, ever. But my dad loved it all.

SPAM was a central holdover from my father’s childhood in Hawaii — a weird comfort food that I assumed they ate because Hawaii only grows pineapples and shipping fresh food across the ocean was expensive. Like I said, I was a kid. That was all I ever needed to know about it. Until the universe needed me to know so much more.

I’ve been thinking about SPAM’s place in my family lore and history, its simplicity, its infamous status as “mystery meat,” and the way it keeps surfacing in my life in new ways, unsolicited. Its resurgence as cult-classic, even haute, cuisine in the last decade or so has made me reexamine its roll in American and global life as well. The only conclusion that I can draw is that SPAM is the perfect zombie idea — it is true apocalypse food that will not die, and seems to perpetually reinvent itself to great acclaim, as social and cultural needs arise.

A Brief History of SPAM

Invented in 1937, by the Hormel meat company in Austin, Minnesota, SPAM was Hormel’s attempt to use more of the pig byproduct that was being discarded in hog processing facilities in the midwest. It is a miraculous seven-ingredient creation: pork shoulder, small amounts of ham (because SPOULDER surely wouldn’t sell), salt, water, sugar, sodium nitrate, and potato starch, all pureed together and extruded into the famous square tin. The last ingredient was only added to the mix in 2009 for a fresher, less sweaty, out-of-the-can appearance.

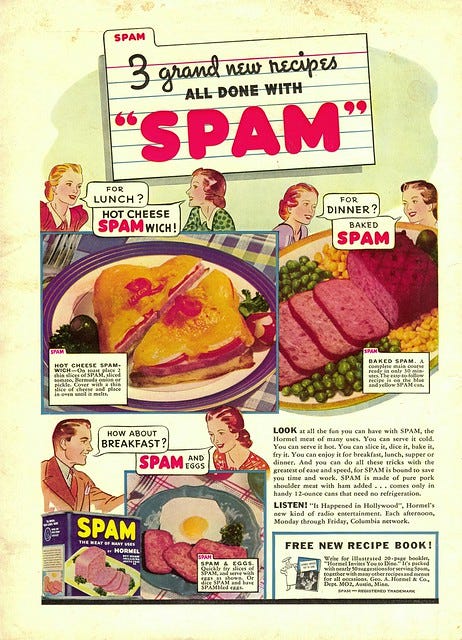

Originally used in peace time like a whole cooked ham or breakfast meat by everyday Americans (see photo), SPAM hit the marketplace just in time to become the main foodstuff for GIs overseas in World War II. It was shelf stable, a decent source of protein, and compact to ship. By 1945, Hormel had shipped 100 million pounds of SPAM abroad to feed American and Allied troops alike. Ultimately, American troops grew to dread it and maligned it to their superiors. But that was when the magic started happening.

Anyplace American GIs were stationed, SPAM was there. It followed the troops across Europe, through the South Pacific, and into southeast Asia through every world conflict with American presence through the 1970s. The GIs’ distaste for it meant that there was surplus available to the often-starving citizens of war-torn countries like Japan, France, Britain, Korea, The Philippines, and Vietnam. It filled a basic human need and was eagerly absorbed into the cuisines of these countries, where it remains a staple to this day. (Check out SPAM UK’s homepage for some of the more interesting uses of SPAM across the pond.)

Even in Hawaii, SPAM became a wartime necessity to the Japanese population there who were denied fishing licenses and the required U.S. citizenship, as a government-directed alternative to mainland internment camps. An entire population was cut off from its main source of protein. SPAM filled the gap.

According to the SPAM® Brand website, 9 billion cans of SPAM have been sold worldwide in 48 countries to date. Hawaii and Guam hold the titles for most SPAM consumed per capita, per annum. In South Korea, a gift of SPAM is considered a great honor. Even North Korea has developed its own state-sanctioned version of SPAM to keep up with the demand among its population.

SPAM as Global Cuisine

In food, good ideas travel fast. Ever since the days of the Spice Road, people have been inherently curious about flavor, texture, and ingredients from other cultures, and have incorporated new finds into their own cuisines to create something better than before — what contemporary foodies call “elevated.”

Some would argue that you can’t possibly polish the scrap that is SPAM into a prize pig. But they would be wrong. If necessity is the mother of invention, it is also the catalyst for great cultural innovation, precisely because of the traits that made SPAM low-brow in the first place. It travels, it’s cheap, and it lasts forever. SPAM is an accidental global culinary success story. Since its incorporation into the cuisines of cultures across the seas, those iterations of SPAM have made their way back to mainland America through generational global migration and the proliferation of social media. Cooks have always experimented with new forms of things that taste “just like home.”

In fine restaurants from New York City to Los Angeles, young chefs are preparing delicacies like a SPAM and foie gras burger, or a haute SPAM Pho’, or a fancied-up Korean buddae jiigae, which translates to “army stew,” a SPAM mainstay of that country’s conflict between north and south that was made from mostly black-market ingredients until the 1980s. SPAM is the ultimate fusion food.

And of course, there is the all-time classic Japanese-Hawaiian crossover that has become a regular on my family’s menu — SPAM Musubi. My friend, Sarah, introduced me to this scrumptious creation only about ten years ago. She thought I must know it because of my family’s Hawaiian history. But I confessed I only had indifferent or slightly-nauseated memories of the can sitting on the high shelf. I am a midwestern girl, after all. Sarah is Taiwanese-American, her husband is Korean-American, and they travel to Hawaii semi-regularly, so it is absolutely a standard dish in their rotation. And it is so ubiquitously loved in Hawaii, some of the best SPAM musubi in the Islands is stocked in the grab-and-go of 7-Elevens.

When done right, SPAM musubi is a beautiful assemblage of a sticky sushi rice base, a perfectly teriyaki-fried slab of SPAM, and a jacket of nori around the outside. The sweetness of the rice, the salty oceanic vibe of the nori, and the caramelized crust of the hot teriyaki around the squishy SPAM make for a total flavor explosion in your mouth. It is a little brick of perfection.

Once my family discovered we liked it, we started having musubi assembly-line parties at Sarah’s. We crank out ten or twelve logs at a time, nigiri-style, while drinking wine and catching up. If we’re lucky, and the kids are adequately distracted, we have some to take home for the next day. It’s a perfect low-key Friday night activity for spending time with friends.

SPAM Save America

So what wisdom can we glean from this seven-ingredient global success in a can? Critics of SPAM’s recent resurgence in popularity call it a harsh reminder of global imperialism and colonization. I always have my anthropologist feelers up for this assessment. It’s an easy one to make when you think solely about the oppressors and the oppressed. But I don’t think it holds in this case. Certainly, America’s role in global conflicts is frequently far from purely altruistic, to be generous. But SPAM did not cause the wars of imperialism of the last century. Rather, it created cross-cultural connection through food in ways that other kinds of diplomacy cannot. What’s more, contact with other world cultures took SPAM from something so profoundly white, midwestern American, and made its story more reflective of the cultures and traditions that actually make up this nation. Isn’t that what the American pluralistic ideal is supposed to be about, after all?

I, for one, am glad this culinary zombie idea keeps rearing its ugly head in such delicious, new, and broadening ways. In the words of Hormel, “Cold or hot, SPAM hits the spot.”

For more of the SPAM®Brand Life (yes, that’s a thing), click here. It’s entertaining, to say the least. This is not a paid endorsement of SPAM®Brand in any way. But make some SPAM musubi. You’ll thank me later. There are recipes literally everywhere online.

So interesting! Believe it or not, despite the fact that I share your Hawaiian family connection, I have never, ever in my life tasted Spam. I guess when Mom (your grandmother) left the islands, she committed to never looking back to Spam as a dinner option! However, she was fond of Oscar Meyer Sandwich Spread, which was a staple in our house growing up. (Hate to admit it, but I still actually like the stuff - do they even sell it anymore???)