My son turns 22 this fall. He is living his best life as a pseudo-adult, expanding his intellectual and social horizons at college, within the safe embrace of his parents’ dole. Lucky boy. He is also looking straight down the barrel of real adulthood. The end of the sweet ride. The cold, hard realities of LIFE.

Like many fledging adults, he is getting a little panicky. He is looking at a grim job market at the dawn of AI. He is witnessing his government behave in a way that is totally counter to what he learned in school about how democracies function. And he is watching big industry destroy the same environment that his generation will inherit, in the name of short-term profits. The world is complicated. It always has been. But Netscape and dial-up did not produce such a constant anxiety loop when I was 22.

My own younger self overflowed with ambition and pluck. In 1995, I was confident that my shiny undergraduate degree carried the promise of a fulfilling career and upward mobility, as long as I worked hard enough when the opportunity presented itself. Then, it was a safe bet. There are no such assurances for today’s college graduates, it seems.

Today, we Gen-Xers often complain that Millennials have no work ethic. We are just old enough that some of us already struggle to stay relevant in the changing work landscape, while the appeal of midlife reinvention is strong. By contrast, the Millennial model holds that 5 side hustles = 1 career (without the longterm commitment). The gig economy is a foundational part of Millennial adulthood, restoring a certain amount of autonomy that is lacking in the standard 9-5 job. But is it working? That same generation struggles to afford to own a home. One generation bet on stability, the other plays with greater self-determination. Neither feels right in a rapidly changing world.

My son’s generation has Gen-X parents and Millennial media roll models. Ease as a life goal has never been more marketed to a generation of people. Those entering the workforce now have been educated and introduced to adulthood through the lens of a global pandemic, when, for a time, work was reduced to its most essential and often optional functions. Digital isolation is one of their core skillsets.

The post-Covid messaging about what work should be is hotly debated and driven by a marketplace where productivity and bottom line are primary, but where humans are rendered less and less crucial and are more and more adrift. Many worry AI will limit human career options to an ever-narrower set of talents. We can all imagine what the world might look like if AI is used to its optimized capitalist potential. So where does that leave the next generation of workers?

There is no going back. Only forward. Given the new parameters, the appropriate questions about work look different: 1) what do we need from work as a human society?; 2) what do we want from work as individuals?; and most crucially, 3) what parts of the future of work are actually within our control?

What is the value of work?

Researchers have long proven the importance of work as a basic human need that promotes overall health. Anyone who has ever been unemployed or underemployed for a significant period of time would probably corroborate this claim. A sense of purpose through paid work seems to be built into the cooperative nature of our species, and certainly into our social constructs of human value. The last two decades have challenged that notion in brand new ways.

In 2014, at the zenith of the gig economy, and just after The Office wrapped its eight-year run mocking the doldrums of modern workplace culture, behavioral scientist Barry Schwartz wrote a book called Why We Work. At the time, Schwartz was determined to provide evidence that, even in increasingly hierarchical and minutiae-driven business environments, there was more to why people work than just a paycheck. The theory he came away with held that it was not human nature to work just for pay, but that, because employers created workplaces that denied workers any of the human satisfaction associated with work, that became the default motivator and driving assumption. Profit before people, and the people will conform.

In 2021, Schwartz revisited that theory for the online journal Behavioral Scientist. The Covid-inspired Great Resignation had just happened, during which 50 million Americans quit their jobs in search of something more fulfilling. It was not merely a rejection of work outright. Work remains a core marker of American self-identity. Rather, it was an enormous social statement that held life is too short for work that you hate. Schwartz observed that, in the face of a global pandemic, Americans started to question the value their work contributed to the world, and their own corresponding sense of personal fulfillment. He said it gave him hope for the future of work that employers were being forced to examine what sense of value they were offering employees beyond pay incentives and longer hours. He called for flattening of hierarchies, fewer supervisors, more personal autonomy among employees to perform the functions for which they were hired, and greater investment in employees’ life needs.

In 2025, the questions about the nature of work are increasingly existential. Schwartz’s observations about the need for an evolved workplace that incorporates human values take on even newer meaning, when the alternative is wholesale replacement. While Schwartz’s suggestions still hold, the rationales for implementing them are morphing, and we have yet to see if employers and employees can handle the growing pains.

The Band-Aid Approach

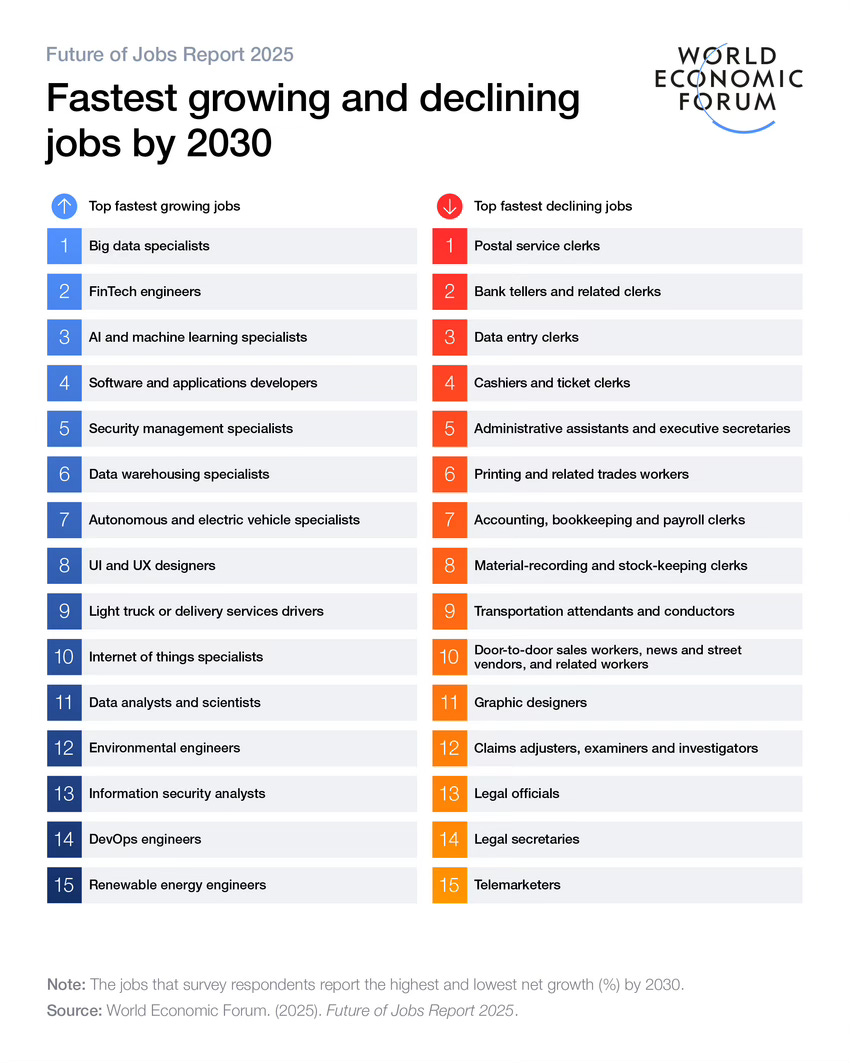

My son is majoring in graphic design. My stomach lurched when he told me he had changed majors — again. According to the World Economic Forum’s Future of Jobs Report for 2025, graphic design will be the 11th fastest profession to be replaced by AI in the next five years. My most optimistic designer friends believe that they can salvage their usefulness by learning to design for AI, to maintain the power of human input. They see AI as a potential collaborator rather than a competitor.

Giving AI a level of collaborative agency (however impossible) seems to be common across industries whose workforce AI will likely render obsolete. In fact, the same WEF report shows that “upskilling” (aka, retraining) is the primary approach businesses plan to take to account for human employee retention after the adoption of AI.

But what does that actually mean? When will this “upskilling” take place? Pre-hire? On the job? Who will pay for it? Historic workplace retraining programs have had limited or poor success rates. There were extremely unique circumstances around the success of the New Deal and the creation of an American middle class. But outside of wartime, subsequent programs of the 1960s, 70s, 80s, and 90s, have had essentially the same failures.

The most recent effort, the Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act of 2014, has been nothing new. It is driven largely by disorganized state jobs boards, and the needs of businesses in those states, not the needs of workers. Previous workforce retraining typically created low-wage, high-stress, dead-end jobs for the country’s most vulnerable workers. Employment, but not fulfilling work, as Schwartz observed. The WIOA is still in place eleven years later, and its goals remain elusive, while reforms are stuck in Congressional committee. With AI, the implications for such a failed program might lead employers to hand more work fully over to AI, regardless of quality.

Can Work Become More Human?

So what is the actual future of work in an AI reality? The challenge for work going forward cannot be a simple repositioning of humans into new utilitarian roles. It calls for a much more inclusive appreciation of uniquely human traits (empathy, resilience, agency, free will, ingenuity) in the workplace, AND a desire to reshape systems that make the workplace run. It requires industries, leaders, and educators to maximize the full spectrum of human capability for the evolution of work. Optimization, as it currently operates, is a driver that leaves too many people out and celebrates the skillsets of a curated few. A better model requires both will and imagination in heavy doses, things that were once considered hallmarks of American ingenuity, but have recently come under attack by anti-intellectualism. We need a solution that speaks to everyone, and one of which our current leadership does not seem capable. But let’s imagine it anyway…

What if AI is a giant RESET button on a system that has served humanity less and less over time? In such a paradigm, AI is an opportunity, not an ominous beginning of cyborg takeover. It is a chance to offload the tedium of modern work life, demonstrate the human resilience of which AI will never be capable, and rethink the entire cradle-to-workforce pipeline for current and future generations across life experiences.

Futurist and AI strategist, Kim Carson, asks a key question along these lines in her April, 2025, talk for the Long Now Foundation. In advocating for the embrace of a protopian model of the future, versus the extremes of utopia or dystopia, Carson asks if perhaps AI is here not to replace us, but rather to remind us of what we are actually capable as humans. It’s a salient point in an era where our own convenience often trumps our desire to think critically and independently. It asks us to examine what parts of our existence we most value.

Next Steps

We are creative beings. We thrive on new knowledge. But in the long view, it appears we are forfeiting those innate gifts to a system where the pace of capitalism often asks us to work beyond our capacity for mental and physical endurance. We have been sold the promise of ease as a foil for that lost autonomy at work and a false measure of happiness. Without future-thinking education, training, skills, and proactive leadership, humans are no more than interchangeable cogs with little sense of purpose in their larger world, in a system that values product over producer.

Just maybe, AI is the solution that allows us to re-embrace the natural pace of actual creativity, intellectual curiosity, and learning. (Hint: it takes time, where less time ≠ more money. Also, it would take a new president.) What if future education was set up to foster these skills in all humans, according to their abilities, and ensure that there was a place for each human to contribute their skills in a more inclusive workforce after that education was complete? What if every person could claim a skillset that is well-suited to them and produces even more innovators across human problem-solving? Imagine what we would be capable of.

There is evidence of these conversations already happening. My son recently added a Design Thinking minor, a relatively new department at his large state university, so that he can be on the right side of AI when he enters the workforce as a designer of the future. Kim Carson continues to broach these topics as CEO of AI Imaginarium, a consulting firm that guides businesses like IBM through the important steps of reimagining work. More broadly, The Center for American Progress is on the right track in its policy discussion called A Progressive Vision for Education in the 21st Century, that consciously links changes in education with changes in worker preparedness. AI must be a central part of the conversation, not just as a threat to overcome, or as a cheat code. It must be a managed tool in creating the work of the future for the ultimate benefit of humanity.

Finally, envisioning this future of work cannot be left to think tanks and policy-makers, and certainly not to business leaders. Again, history does not bear it out. This is Step 1 of embracing our individual capacities for creativity, independent thought, and critical thinking. Anyone can have an idea. No one needs permission. Anyone can imagine a better future from where they are right now, no matter how small the movement of the needle. Anyone can be a leader. Our voices and our curiosity are the instruments for bringing creativity to life. Ideas are meant to be shared. What do you want for the future of your own work?

Have a great week.

-IWW

Up Next: De-centering the Human in AI Thinking

Ok. So I did my best to make friends with AI. I did the thought experiment, the reading. I saw the possibilities. I found the use-cases. I even found potential advantages for humanity. But what happens when the best answer to new tech is no tech at all? How AI might kill us faster…

I'm gratified to hear that they're teaching a "creative thinking" course at a state university. My growing concern is that, with the current disregard for quality education in DC, that kind of forward thinking curriculum may eventually only exist at private schools. The vast majority of young college-age people are finding tuition out of their reach. If only the well-healed can attend such schools, what happens to the young people with creative/abstract thinking DNA who are priced out of that education? Scholarships are great, but there aren't nearly enough. I don't know what the answer is, but I think about it every day.

I think it's possible that the AI bubble will burst or, rather, slowly leak ... and the market will evolve. It's not the worst if AI does the tech stuff and we get to do the human stuff. That's how I see it. Until we figure this out, it's going to be rough ... our girls are in college now. I think they have chosen majors that have strong job opportunities (special education and exercise science focusing on allied health). But it will be interesting how AI will impact their careers.